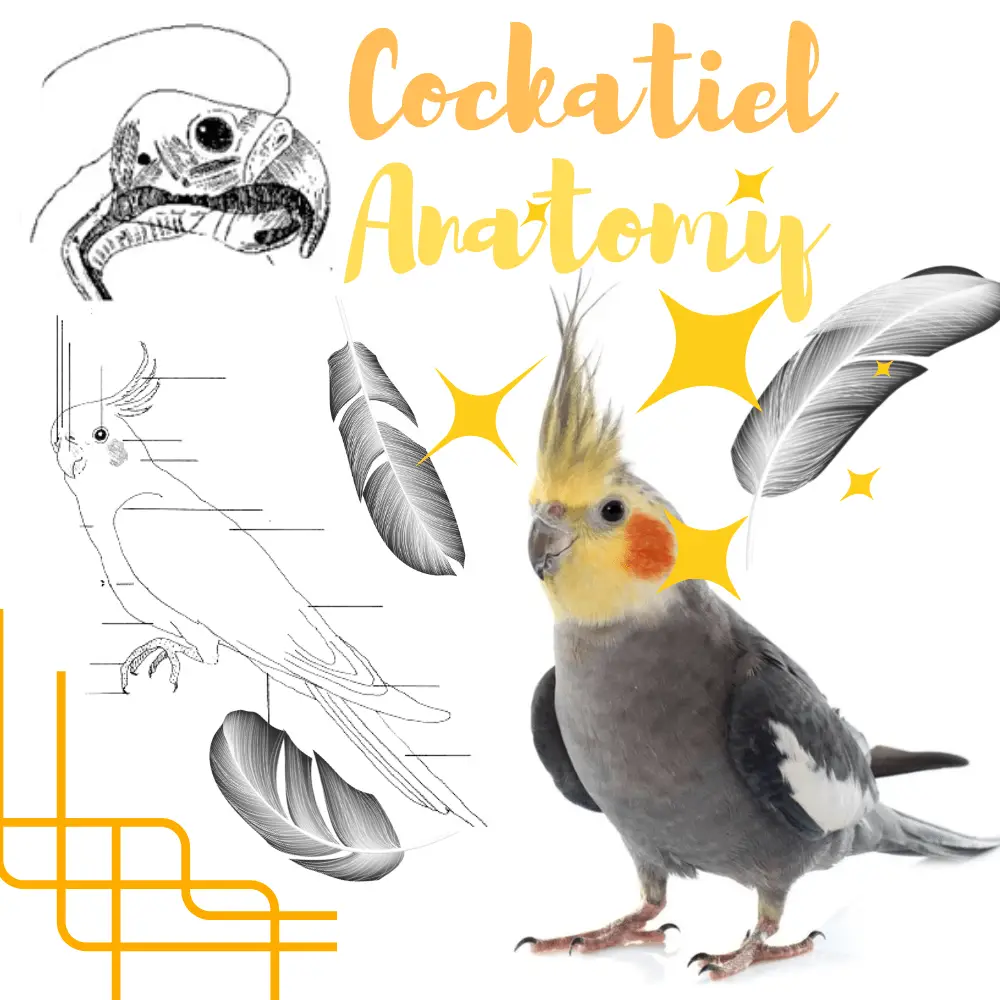

Cockatiel Anatomy: All you need to know about Cockatiel Head, Cockatiel Beak, Cockatiel ears, Cockatiel body,

cockatiel plumage, The eye of the cockatiel and that of man are identical, unlike the pecten, which is very vascular in birds.

Cockatiel Head

Cockatiel Anatomy

Physically, the cockatiel has a gray-colored body, with white stripes on the wings. But its primary particularity is its head, yellow in color, with round orange spots on the cheeks, and its crest located on the top of its skull, which allows it to be very expressive.

Cockatiel Beak

Cockatiel Anatomy

The eye of the cockatiel is adherent to the bottom of the orbit and therefore always fixed. To compensate for this handicap, he is endowed with significant mobility. The bird blinks very little. Vision is monocular, which means that each eye can see independently of the other. This gives the cockatiel a very wide field of view.

Cockatiel Ears

The ears of the cockatiel do not have a pavilion. They are located behind the eye and the eardrum protrudes outwards.

Cockatiel Body

Physically, the Calopsitte parakeet has a gray body, with white stripes on the wings. But its first peculiarity is its head, yellow in color, with round orange spots on the cheeks, and its crest located on the top of its skull, which allows it to be very expressive. There are also many color mutations in captive-bred species.

The Calopsitte parakeet measures between 30 and 40cm, weighs between 80 and 150grams, and lives between 10 and 20 years on average.

The skin of the Cockatiel

The skin of the cockatiel is thin and adheres to the bone structure. The bird does not have sweat or sebaceous gland (with the exception of the external auditory canal and the uropygial gland – located on the rump above the elevating muscle of the tail – whose role is to allow the coating of feathers with lipid secretion for waterproofing purposes).

The fingers of the cockatiel

The fingers of the cockatiel parakeet have a zygodactyl layout, which is the characteristic of idle climbers: fingers II and III are directed forward, and fingers I and IV are directed backward. Each finger ends with a keratin claw.

The legs of the cockatiel

They are cross-linked, stocky, and covered with scales.

The plumage of the cockatiel

The plumage represents no less than 10% of the bird’s body.

Each feather has a limited lifespan after which it falls off to be replaced. The molt lasts between 6 and 8 weeks, and the loss of feathers is organized gradually and symmetrically on the body. This represents a tiring period for the animal: the bones are more prone to fractures because molting pumps on the calcium reserves of the cockatiel. They are implanted on the body of the animal according to a mapping that never deviates according to lines called “pteryliies”, and develop in a sheath called “matrix cylinder”.

There are several different types of feathers:

- The pinnae, also called “contour feathers”: are the primary remiges of the hand, the secondary on the forearm, the rectrices of the tail, and the tectrices of the body.

- Semi-feathers: this is the “down” of the cockatiel. They are located around the eye, around the eyelids, beak, and nostrils.

- The plumules: are under the pennies and are used for waterproofing and thermal insulation of the bird.

- Powdery down: these small feathers with continuous growth see their end reduced to a floury powder based on keratin. They are found at the top of the thighs and are used to smooth and waterproof the plumage.

The internal organization of the cockatiel

The skeleton of the cockatiel

The cockatiel has between 120 and 170 bones, some of which are welded together and the majority of large bones have a hollow central part and are devoid of marrow (pneumatized bone: the majority of vertebrae, sternebrae, pelvic bones, and ribs).

The cavity of the pneumatized bones is in communication with the respiratory system via the tubules. Bones are composed of 33% organic matter and 67% mineral matter. cockatiels are particularly susceptible to head trauma: indeed, the skull is composed of 9 very thin bones. The sternum and its breech are the main attachment point of the pectoral muscles.

The breathing apparatus of the cockatiel

Like the rest of its anatomy, the bird’s respiratory system is particularly suitable for flight. The cockatiel does not have a diaphragm or epiglottis in the larynx. The lungs occupy no less than a third of the dorsal space of the rib cage, the air sacs of which constitute an extra-pulmonary extension.

These air sacs are 6 in number and represent 20% of the body volume of the animal. They are extendable and serve both as bellows in pulmonary ventilation, thermal insulation, as an air tank during take-off or singing, viscera insulation, or even to lighten body weight.

The digestive system of the cockatiel

The transit of the animal is fast: less than 8 hours. Food passes in the first place from the beak to the crop. This portion located at the entrance of the chest serves as a transition between the mouth and the stomach and expands to accommodate food thanks to a thin wall composed of smooth muscles. The content of the crop is called “ingluvial content”.

The main role of the jabot is to regulate transit by storing them to redistribute them to the stomach as and when needed. When feeding young cockatiels, the crop undergoes retrograde peristaltic contractions allowing the regurgitation of food.

The bird has two stomachs: the proventricle and the gizzard.

Digestion concludes with the exit of the cloaca of brown-green droppings with a white part and firm consistency. Urine forms crystals of urates of white or cream color. The bird does not have a bladder: urine is ejected at the same time as a stool. The number of daily droppings amounts to several dozen per day.

Near the cloaca, the Fabricius bursa is a vesicle with a large diameter in young animals: it is the place of maturation of T lymphocytes, and therefore crucial in the course of the immune system.

The heart of the cockatiel

Compared to mammals, the heart of the bird is singularly large. It is not in direct contact with the lungs but rather located on the ventral part, enclosed by the two lobes of the liver. The heart of the cockatiel is surrounded by a fibrous pericardium containing a lubricating liquid, and its right jugular vein is larger than the left.

The walls of the veins are fragile: this is the reason why the animal is particularly sensitive to hematomas.

The reproductive system of the cockatiel

If the male cockatiel has two intra-abdominal testicles, he does not have phalluses or ancillary sex glands. If the testicles are small outside the breeding season, they increase significantly once it comes: from 300 to 500 times. The male’s testosterone is directly related to the pituitary gland, which is itself impacted by the variations in light received by the optic nerves and hypothalamus.

In adult females, only the left ovary and oviduct are functional, with the right part atrophied. During the breeding season, as for the male, the oviduct of the female increases to a volume 300 times larger than her size out of the breeding season, until it occupies most of the left abdominal cavity.

The temperature of the egg in the oviduct is 42 ° C and the transit time of the egg until laying lasts about 25 hours. Females usually lay one egg every 48 hours on average under good breeding conditions.

After the laying of eggs, the presence of a high level of progesterone prevents the production of additional eggs, and the genital tract regresses: this is the brooding period.

During copulation (the “ticking”), the cloaca of the male comes into contact with the turned cloaca of the female.

Anatomy of a cockatiel Parrot

SOURCE:Paulina Moneta