The New Zealand kaka parrot is a species of the family Nestoridae found in native forests of New Zealand

Psittacus meridionalis Gmelin, Syst. Nat., 1, pt. 1, 1788, p. 333. (New Zealand = Dusky Sound, South Island, ex Latham.)

OTHER NAME Kaka Parrot

New Zealand kaka

DESCRIPTION Length 45 cm. Weight males 383–575 g, females 494–500 g.

ADULTS Forehead, crown, and occiput pale greyish-white, almost white and feathers sometimes margined dull green; nape greyish-brown, feathers marked olive-brown; neck and abdomen brownish-red, noticeably more crimson on hindneck where feathers finely tipped yellow and dark brown

breast olive-brown; ear-coverts orange-yellow; back and wings greenish-brown, on mantle some feathers tipped red; tail-coverts crimson barred dark brown; underwing-coverts and undersides of flight feathers scarlet; tail brownish, tipped paler; brownish-grey bill longer and more curved in male; iris dark brown; legs dark grey.

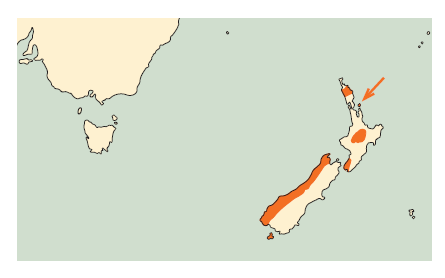

DISTRIBUTION

New Zealand, were present on the North, South, and Stewart Islands, and some offshore islands; formerly on the Chatham Islands.

New zealand parrots

SOURCE: Henry the PaleoGuy

SUBSPECIES

The nominate subspecies, as described above, occur on South Island, mostly west of the Southern Alps, on Stewart Island, and on some offshore islands, including Big South Cape and Codfish Islands and the Chetwode Islands.

2. N. m. septentrionalis Lorenz Nestor septentrionalis Lorenz, Verh. zool.-bot. Ges. Wien, 46,

1896, p. 198. (North Island, New Zealand.)

ADULTS overall plumage coloration duller; forehead, crown, and occiput dull grey; back and wings darker olive-brown, feathers edged darker brown; breast darker brown; less crimson on hindneck; slightly smaller size; weight males 320–555 grams, females 210–455 grams.

- males: wing 267–272 (269.4) mm, tail 140–161 (152.1) mm, exp. cul. 41–50 (46.6) mm, tarsus 34–36 (35.0) mm. 7

- females: wing 256–271 (263.0) mm, tail 140–154 (150.6) mm, exp. cul. 39–44 (41.3) mm, tarsus 33–37 (35.1) mm.

Occurs on North Island, and some offshore islands

kaka parrot

STATUS Subfossil material indicates that New Zealand Kaka was widespread and common throughout North Island, South Island, and Stewart Island, and they were abundant at the time of European settlement, but by the early 1900s, they had declined to localized flocks (Heather and Robertson 2015).

Buller (1888) noted that they were ‘met with, more or less in every part of the country’, and it was claimed that thousands were killed when large flocks came to feed on favored seasonal foods, such as nectar from flowering rata Metrosideros robusta.

They were widely hunted by Maori for food and for feathers used to make cloaks, and principal methods of capture were with snared perches placed around a decoy bird or spearing and striking birds attracted by a decoy (in Oliver 1955).

However, it is widespread land clearance following European settlement and the introduction of mammalian predators that were responsible for dramatic declines in numbers.

Clearfelling of native forests, competition from introduced Brush-tailed Possums Trichosurus vulpecula and rats for fruits,

competition from introduced Vespula wasps for honeydew, and predation by introduced mustelids have been identified as major causes of strong declines in local populations. Nesting females are killed more easily by mustelids and possums, so producing the very skewed sex ratio in favor of males recorded in many populations on the main islands (Heather and Robertson 2015).

Beggs and Wilson (1991) report that at Big Bush State Forest, in the north of South Island, between November and early January in each year from 1985 to 1990, at a site in Nothofagus forest modified by introduced browsing mammals, field studies were undertaken to examine factors influencing the ability of Kaka to breed successfully where habitat quality has been reduced by introduced browsing mammals and Vespula social wasps, and where introduced predators are present. These investigations were undertaken because of earlier studies of a remnant population on

South Island had suggested that energy may be a limiting factor for the following reasons: Kaka may expend more energy than they gain while obtaining one of their major protein foods, larvae of Kanuka Longhorn Beetles Ochrocydus huttoni, which are extracted from the trunks of living mountain beech Nothofagus solandri, Nothofagus forests have a small range

of foods with a high net energy return, and this range is reduced further by browsing mammals such as possums, (iii) the availability of the major remaining source of energy, honeydew produced by the scale insect

Ultracoelostoma assimilate is greatly reduced by introducing Vespula wasps at certain times of the year.

Of the 31 birds fitted with radio transmitters during the six years of the study, only two pairs attempted to breed, and only one of these attempts was successful with two chicks fledging.

The only successful nest was protected by wrapping aluminum sheeting around the trunk of the tree to exclude mustelids, but the female from this nest used a different site the next year and was killed, presumably by a Stoat Mustela erminea.

Not only was Kaka absent when wasps were numerous, but no birds fitted with radio transmitters were also seen feeding on honeydew, so for about four months of the year the presence of wasps reduced the energy value of honeydew

and probably the potential feeding rate, that honeydew was no longer a worthwhile source of energy for the parrots. It is suspected that this loss of honeydew as an energy source was the reason for only one successful nesting in the six years of the study.

Beggs and Wilson point out that, although the life expectancy of Kaka is not known, successful breeding by only one pair of 31 birds in five years is a low reproductive rate for even a long-lived species, and is unlikely to compensate for mortality by predation.

On North Island, Kaka now is either absent or rare in most regions, with remnant populations restricted to larger tracts of podocarp-hardwood forest in central districts and some predator-free offshore islands, and on South Island, mostly west of the Southern Alps, they are widespread, though in declining numbers, through larger tracts of Nothofagus and podocarp-hardwood forests (in Powlesland et al. 2009).

While intensive and sustained pest control has dramatically improved the density and sex ratio of populations in a few districts where mammalian pest control is carried out, Kaka is declining throughout the remainder of the range.

It is estimated that in the past 100 years there has been a decline of approximately 60 percent in the total population and in habitat area, and the present population is estimated at 1000– 5000 mature individuals.

Subfossil remains, possibly of this species, were recorded on the Chatham Islands, where the birds are thought to have become extinct before 1871 (in Higgins 1999).

HABITATS Kaka is forest birds, frequenting mostly unmodified indigenous, temperate rainforest, but occurring also in low broadleaf forests comprising trees such as Tawa Beilshmiedia Tawa, hinau Elaeocarpus dentatus, kohekhe Dysoxylum spectabile, rata Metrosideros excelsa and kamahi Weinmannia racemose, usually with much epiphytic growth

and a diverse undergrowth featuring a prevalence of ferns, and tall podocarp forest dominated by totara Podocarpus totara, rimu Dacrydium cupressinum, rata, miro Prumnopitys ferruginea and matai P. taxifolia (in Higgins 1999).

They have been recorded also in Nothofagus forests with sparse understorey or mixed podocarp-broadleaf-beech forests, but rarely in Leptospermum scrubland or logged areas, including stands of dense regrowth.

They usually do not adapt to altered landscapes, but small numbers may remain in remnant patches of forest, and occasionally venture into farmlands, orchards, and urban gardens or parklands, the last being utilized more commonly on Stewart Island.

kaka parrot

Between 1996 and 2002, studies of nesting behavior were undertaken at two sites on North Island and two sites on South Island (Powlesland et al. 2009).

The first study site on North Island was in a stand of dense podocarp forest at Pureora Forest Park, where the tall forest cover consisted of emergent podocarps, particularly rimu, kahikatea Dacrycarpus dacrydioides, and matai, over a canopy of mainly tawa.

At the second study site in Whirinaki Forest Park, the forest comprised mainly tall stands of podocarp and hardwood trees, such as emergent rimu, with scattered kahikatea, matai, and miro, again over a canopy of mainly Tawa, while on some exposed ridges and slopes the podocarp-hardwood forest was replaced by a mixture of rimu, miro, red beech Nothofagus fusca and Hall’s totara Podocarpus hallii.

At the first study site on South Island, comprising 825 ha of beech forest on the western side of the St Arnaud Range and bordered partly by farmland and Lake Rotoiti, the lower slopes were dominated by red beech and silver beech Nothofagus

menziesii, with mountain beech N.

In Fiordland National Park, the second study site on South Island was in the Eglinton River Valley, a steeply-sided valley with a 0.5–1.0 km wide flat floor

where open, grassy areas were near the river, and elsewhere, up to 1000 m elevation, the covering forest comprised pure stands of silver beech along the margins giving way to stands of red beech farther into the forest, with mountain beech occurring occasionally in the canopy at low altitudes and becoming more common with increased altitude.

At all four study sites, an important component of the forest canopy was formed by masting tree species that produce a superabundance of fruits or seeds at irregular intervals of one to seven years, but little or no fruits or seeds in intervening years.

Moorhouse (1997) points out that on Kapiti Island, where foraging studies were undertaken, a diverse mosaic of indigenous forest and shrubland covers 81 percent of the island, and dominant tree species include five-finger Pseudopanax arboreus, kanuka Kunzea ericoides, kohekohe Dysoxylum spectabile and tawa Beilschmiedia tawa.

Also common are hinau Elaeocarpus dentatus, karaka Corynocarpus laevigatus, and mahoe Melicytis ramiflorus, with northern rata Metrosideros robusta and pukatea Laurelia novae-zelandiae occurring as scattered emergents.

MOVEMENTS Kaka wander about, though this was more regular in earlier times when they were more common and widespread, and then they could appear suddenly in an area from which they had been absent for some time.

Roberts (1953) reported that the lightkeeper on Burgess Island, in the Mokohinau Group, claimed that they passed through the island at a certain time of the year and perched near the lighthouse for only one day before moving south the following night.

They commute freely between the northern islands and wander to coastal forests and towns on North Island (Heather and Robertson 2015).

Also on North Island, translocations to Zealandia Wildlife Sanctuary and Pukaha Mount Bruce National Wildlife Centre have been successful, with the local population currently estimated at 200 to 250 birds, and now Kaka commonly is encountered in suburbs of nearby Wellington.

One bird reared in Zealandia Wildlife Sanctuary dispersed to Pukaha Mount Bruce National Wildlife Centre, 100 km to the northeast, before returning to the Sanctuary (Miskelly et al. 2005).On South Island, birds occasionally come east of the Southern Alps into coastal Canterbury and Otago.

HABITS In pairs or small parties of up to 10 birds, Kaka are highly conspicuous when in flight above the forest canopy, but when sitting quietly in the treetops or feeding alone amongst the foliage they can be difficult to detect, their presence often being betrayed only by occasional calling or by discarded food scraps falling to the ground underneath.

Beggs and Wilson (1991) report that at Big Bush State Forest, in the north of South Island, the daily activities of 31 birds fitted with radio transmitters were monitored, and it was found that they were active from at least 30 minutes before sunrise to 30 minutes after sunset.

For males, time spent sleeping was almost 10 hours in summer and slightly more than 12 hours in winter, time spent perching was six hours in summer and almost three hours in winter, time spent walking was one hour in summer and 30

minutes in winter, time spent flying was only 30 minutes in summer and 10 minutes in winter, time spent extracting beetle larvae from tree-trunks was three hours in summer and four hours in winter, and time spent foraging for other foods was five hours in summer and very slightly longer in winter.

For females, time spent sleeping was nine hours in summer and a little more than 12 hours in winter, time spent perching was five hours in summer and about 90 minutes in winter, time spent walking was about 90 minutes in summer and about 40 minutes in winter, time spent flying was approximately 40 minutes in summer and about 20 minutes in winter

and time spent foraging for other foods was about eight hours in summer and approximately nine hours in winter, but no females were observed extracting beetle larvae from tree-trunks. Heather and Robertson (2015) note that Kaka delight in acrobatics and aerobatics, jumping through the trees using the bill as an extra appendage when climbing, and tumbling through the air for enjoyment.

There are reports of highly conspicuous pre-roosting flights becoming common towards nightfall, and Sibson (1947) noted that at each evening on Little Barrier Island, while some birds stayed behind and called continuously from the forest, parties of eight to 12 birds would fly from the flat high over the ridges and sometimes out to sea and back.

On Kapiti Island, these parrots are remarkably tame and will accept food from the hands of visitors to the sanctuary. Males can be intolerant of a near approach of other males, especially in the vicinity of the nest.

Threat displays usually are subtle, such as turning to face the oncoming bird, but at times this is accompanied by harsh calling and lifting the wings to display the red underwing-coverts (in Higgins 1999).

CALLS Kaka is more vocal in the early morning and at dusk, and outside the breeding season, little calling is heard at other times. Their calls comprise a wide variety of melodious whistling notes and harsh grating sounds.

The most frequently heard call is a loud, harsh ka-aa usually given in flight, and contact calls comprise high-pitched, usually monosyllabic whistles and warbles ranging in volume from loud to muted.

A harsh, loud Kraak is given when alarmed, and a harsh, but muted ngaak-ngnaak in disputes between feeding birds. Feeding may be accompanied by low musical karrunk notes.

When indicating a potential nesting site to the female, a male gives a high-pitched squeaking tseetsee-tsee, and when soliciting food from the male, a female utters a loud, harsh whining kree-kree, interspersed with a guttural AAAA (in Higgins 1999).

new zealand parrots

DIET AND FEEDING The varied diet comprises fruits, seeds, nectar and honeydew, sap from tree-trunks, and insects and their larvae.

Kaka uses their strong bills to crush seeds and to tear away loose bark or dig into decaying tree-trunks to extract larvae of woodboring insects or to feed on exposed sap, and use their brush-tipped tongue to take honeydew excreted by scale insects or nectar from flowers (Heather and Robertson 2015).

Moorhouse (1997) reports that on Kapiti Island, between March 1991 and January 1992, the food of Kaka was recorded while observing the foraging activities of nine radio-tagged birds.

The proportion of time these birds spent foraging relative to other activities varied considerably from month to month, increasing from March to June and from September to November, and there was marked seasonal variation in the diet. Although most birds foraged primarily for wood-boring insect larvae, on seeds of hinau Elaeocarpus dentatis.

Two males continued to feed primarily on hinau seeds until June, but all females stopped eating them after March. Most birds spent about 30 percent of their observed foraging activity feeding on nectar or pollen from five-finger Pseudopanax arboreus in August and nectar and pollen from a variety of sources between November and January.

Foraging for seeds of tawa Beilschmiedia tawa also increased in this same November to January period. Little of the observed foraging activity was devoted to taking fruits and, although most birds fed on fruits of hinau and tawa later in the year, they usually spent less than 12 per cent of their observed foraging activity on these foods.

Only one bird was seen to take fruits of five-finger, but nestling faeces frequently contained these seeds, indicating that it was fed to nestlings.

Invertebrates eaten on Kapiti Island included coleopteran and lepidopteran larvae, probably of kanuka longhorn beetle Ochrocydus huttonii and puriri moth Charagia virescens, extracted from dead branches and live wood, larvae of an undescribed gall midge extracted from galls, six-penny scale insects Ctenochiton Viridis gleaned from leaves, and unidentified invertebrates, possibly including nymphs of Hemideina tree-weta extracted from dead twigs.

Beggs and Wilson (1987) report that during field studies undertaken at Big Bush State Forest, in the north of South Island, Kaka was found to spend 35 percent of their feeding time digging into the trunks of mountain beech Nothofagus solandri to extract the larvae of kanuka longhorn beetles and an unknown amount of time searching for these larvae.

When extracted, a majority of these large larvae were at their most vulnerable stage, packed into pupal chambers and unable to escape into lower portions of their tunnels.

They were also more easily detected at this stage by the plugged exit hole on the surface of the tree trunk.

To extract a single larva, a parrot spent up to two hours of vigorous activity while clinging to the vertical tree-trunk, so it was hypothesized that more energy was expended obtaining one larva than was gained by eating it and that the parrots would need to balance their energy budget by gaining energy from other more energetically economic food such as seeds, fruits or honeydew.

At Big Bush State Forest, the main alternative food was honeydew excreted by the scale insect Ultracoelostoma assimilate, and in spring, when the average feeding time for Kaka was nine hours, the three hours of this time spent taking honeydew was sufficient to give them most of their daily energy requirements (Beggs and Wilson 1991).

Sap-feeding by Kaka is concentrated in late winter and spring when very few nectar sources are available, temperatures are lower and energy demands are high. O’Donnell and Dilks (1989) point out that parrots use two distinct techniques to feed on sap.

They strip bark from a branch or trunk to expose the surface cambium and then lick the sap exudate from the surface. With the second, more specialized technique, a parrot starts by peeling and discarding loose bark from a tree-trunk. It then uses the lower mandible to prise a ‘trapdoor’ through the remaining bark and to gouge a series of tiny holes into the superficial layer of yellow cambium some 6–10 mm below the surface.

At times, when hanging upside down, a bird will lever the ‘trapdoor’ downwards. The resulting horizontal marks are very distinctive, occurring on trunks and large branches from ground level up to high in the canopy, and they persist for a very long time, prompting the suggestion that old scars on large trees could date from pre- European times.

O’Donnell and Dilks recall that in early August 1984, in South Westland, South Island, sap-feeding by two parrots was observed for almost an hour, and spells of prising away bark averaged 6.6 minutes, with intervening times spent revisiting older scars to extract sap which had leaked from the wounds.

An average of 1.8 minutes was spent licking up sap, and one new scar was visited at least four times in the period of observation. Sap feeding has been recorded at both native and introduced trees, and Charles (2012) notes that trees with very few scars have been found near to heavily-scarred trees, suggesting that the parrots may test a number of trees before selecting a preferred tree for feeding.

In native forests, sap-feeding has been recorded mostly at Myrtaceae trees, southern rata Metrosideros umbellata and Metrosideros hybrids, kanuka Kunzea ericoides, rimu Dacrydium cupressinum, matai Prumnopitys taxifolia,

Tawa Beilschmiedia tawa, totara Podocarpus totara, and conifers, but it is not known why these trees are preferred, with a higher sugar concentration or easier access to sap being suggested as possible reasons.

In the Wellington district, North Island, tree damage from sap-feeding by Kaka in the population originating from successful translocation has been recorded predominantly in introduced conifers and eucalypts, and mainly in large mature trees.

Charles and Linklater (2014) report that in order to determine the characteristics that make trees prone to sap-feeding by Kaka, a total of 282 trees were sampled in 45 groups at 15 sites across Wellington city, and these sampled trees were of 31 different species, 12 of which were not native to New Zealand.

The damage was recorded on 85 trees of 10 species, and exotic trees, particularly conifers, were significantly more likely to be damaged than native trees.

In this study, half of the species observed with damage were conifers, and more than 80 percent of individual trees were conifers, including macrocarpa Cupressus macrocarpa, Lawson’s cypress Chamaecyparis lawsoniana, and Japanese cedar Cryptomeria japonica.

The extent of damage ranged from an estimated 2.5 to 60 percent of bark-cover but predominantly was low, with damage to 64 percent of damaged trees between 2.5 and 10 percent. Most damaged trees had bark removed from the trunk only and damage occurred mostly on the upper third of the tree.

Diameter at breast height was the most informative characteristic for predicting damage and was highly correlated with tree height.

Damage from sap-feeding was more likely to occur on taller trees with a wider girth. Topographic exposure was the second most influential characteristic for predicting damage, with trees on more exposed sites, such as ridges or steep hillsides, more likely to be damaged than trees in valleys.

Charles (2012) points out that in this urban situation tree damage is of concern because there is a higher risk of branches falling from damaged trees, especially during high winds.

BREEDING What is known of the breeding biology of Kaka comes mostly from field studies undertaken between 1996 and 2002 in central North Island, at Waipapa Ecological Area of Pureora Forest Park and in Whirinaki Forest Park, and in the Rotoiti Nature Recovery Area, in the north of South Island, and in the Eglinton River Valley in Fiordland National Park, in the far south of South Island (Powlesland et al. 2009).

The proportion of radio-tagged females that nested at a site in a given year varied from none to all, with most nesting occurring in years of mast-fruiting or seeding by preferred food trees, and most nests were in natural hollows in the trunks of live canopy or emergent trees.

At the two sites in North Island, 75 of the 97 nests were in matai Prumnopitys taxifolia or rimu Dacrydium cupressinum trees with a mean height of 34.1 m and a mean trunk diameter at breast height of 128.8 cm.

Nests were at a mean height of 12.6 m, and the mean dimensions of hollow entrances were 551 mm in height and 120.6 mm in width. Nesting chambers were at a mean depth of 780.3 mm in the hollows, and the mean diameter of these

chambers was 912.2 mm at one site, but only 473.2 mm at the other site. At the two sites in South Island, all but two of the 71 nests were in the dominant Nothofagus trees with a mean height of 24.6 m and a mean trunk diameter at breast height of 111.5 cm.

Nests were at a mean height of 10.4 m, and the mean dimensions of hollow entrances were 452 mm in height and 88.3 mm in width. Nesting chambers were at a mean depth of 666.6 mm in the hollows, and the diameter of these hollows was measured at only one site, where it was 573.1 mm.

Each female energetically grubbed to a depth of 50–100 mm into dry rotten wood on the floor of the chamber and supplemented this material with live or dead wood chewed from walls of the cavity, biting and chewing large pieces to form a well-aerated dry tilth in which she scraped a nest-bowl about 300 mm in diameter and 20 mm deep.

At the Rotoiti site, northern South Island, prior to egg-laying, on seven occasions over two days, a male was seen to enter the nesting hollow while the female was inside, each time remaining inside the hollow for one to two minutes, and this was the only record at any of the study sites of a male entering an occupied hollow, including during periods of incubation and care of the nestlings. Copulatory behavior was observed on several occasions at each of the study sites.

Prior to mounting, the male walked up to the female several times, gently nudging her with his bill and forehead or with afoot. In response, the female assumed a soliciting posture, with the back flattened and head lowered while the wings were slightly drooped.

The male then mounted and, with flapping wings to maintain balance, assumed the copulatory position, cloaca to cloaca. For up to 15 minutes, the male maintained a slow, rhythmic wing-flapping together with unsteady movements of his body.

During copulation, the female raised slightly her head and tail, and the male knocked his bill against hers during each unsteady body movement.

Although the male remained mounted throughout copulation, cloacal contact probably was only briefly during each unsteady body movement. The female often uttered a soft, high-pitched squeaking throughout copulation. After dismounting the male perched motionless beside the female for several minutes before

flying away.

The commencement of egg-laying at each study site varied by up to a month. At the two sites in North Island and at the Rotoiti site in South Island there were very few records of egg-laying commencing in October, and peak times were in November and December, but at the Eglinton site in Fiordland, far southern South Island, the first records were in December and peak times were in February. Of 83 clutches, there was one clutch of a single egg, five clutches of two eggs, 17 clutches of three eggs, 24 clutches of four eggs, 29 clutches of five eggs, three clutches of six eggs, one clutch of seven eggs, and three clutches of eight eggs.

Video-taping of the laying of a clutch of four eggs revealed that the interval between laying of the first and second eggs was 3.8 days, between the second and third eggs was 3.2 days, and between the third and fourth eggs was 3.7 days.

The moment of laying was preceded by pelvic movements, hunching of the back, and fanning and depression of the tail. Soon after each egg was laid, the female circled around and, with her bill, gently moved it under her body.

Incubation by females lasted 20 to 23 days, and video monitoring of four incubating birds revealed that females left the nest a mean of 13 to 17 times, with eight to 12 of these absences being in the daytime.

On average, females incubated for 73 to 109 minutes between absences, and were absent for a mean of four to six minutes per absence, with a range of one to 62 minutes. Males occasionally alighted at the nest entrance and looked inside, but did not enter the hollow.

The male of a nesting pair normally approached to within about 20 m of the nesting tree and called, causing the sitting female to emerge from the nest, and then both birds flew to a perch some 50 m from the nest, where the female was fed regurgitated food by the male. Females invariably returned to their nests after only a brief absence.

The time of hatching for each egg was determined for a clutch of four eggs and for a clutch of five eggs and, assuming that eggs hatched in the order that they were laid, intervals between the hatching of the first and second eggs were 0.3 and 0.4 days,

between the second and third eggs were 1.2 and 0.3 days, between the third and fourth eggs were 1.3 and 3.3 days, and between the fourth and fifth eggs was 1.0 day, to give a mean hatching interval of 1.1 days. Newly-hatched chicks are covered with white down and, when not being brooded by the female, they huddled closely together, raising their heads only when stimulated by the female. While the nestlings were less than 10 days old,

females were absent from the nest two or three times during the night and 12 or 13 times during the day for periods of seven to 25 minutes, but the chicks were not fed at night even though females often were absent from the nest for extended periods.

Between 11 and 20 days, nestlings developed a dense covering of grey down and the eyes were partially open. At this time, the mean number of absences of females at night ranged between two and six of 23 to 124 minutes duration, and during the day ranged between nine and 16 of 35 to 93 minutes duration. After 20 days, there was little brooding of the chicks by females, and between 21 and 30 days eyes of the chicks opened fully and flight feathers began to extend beyond the down,

with little change in absences from the nest by females from those of the previous 10 days. At 31 to 40 days, the chicks were partially feathered, and females were absent from the nests for 49 to 82 percent of the time.

At 41 to 50 days, the chicks were fully feathered and, assuming that chicks fledged in the order of hatching, the fledging age for a brood of four chicks were calculated at 64.8, 70.3, 72.1, and 69.5 days, and for a brood of two chicks at 67.9 and 68.2 days.

Fledglings initially were poor fliers, sometimes ending up on the ground and remaining there for three to four days, usually attempting to hide under low vegetation or fallen logs, before climbing into the canopy or flying away.

Nestling survival rates at the two sites on North Island and the Rotoiti site on South Island were similar, ranging from 48.4 to 57.9 percent, but there was considerable variation between breeding seasons at each site.

A much higher success rate of 80.9 percent was recorded at the Eglinton site in Fiordland, and there was very little variation between the two seasons for which data were available.

Although an occasional brood died of starvation or exposure when a cavity was flooded during heavy rain, the main cause of losses was mammalian predation of eggs and chicks, and video footage was obtained of chicks being killed by Stoats Mustela erminea and Brush-tailed Possums Trichosurus vulpecula. It was suspected that the much higher success rate at the Eglinton site in Fiordland could be attributed to the low density of possums, stoats, and rats during the two seasons of the study.

The benefits of effective predator controls on nesting success have been demonstrated at other localities. At Zealandia Wildlife Sanctuary, near Wellington, North Island, where pairs nested within a site fenced to exclude mammalian predators and where supplementary food was supplied, 57 percent of 84 eggs produced fledglings, and at nearby Pukaha Mount Bruce Wildlife Centre, where nesting also took place at predator-free sites and with the provision of supplementary food, 40.7 percent of 167 eggs produced fledglings (in Powlesland et al. 2009).

Eggs are slightly oval in shape and with a slightly rough surface. Measurements of 12 abandoned or infertile eggs of N. m. septentrionalis taken from seven nests in Whirinaki Forest Park, North Island is 41.5 (40.2–44.4) × 31.5 (30.1–33.0) mm

(Powlesland et al. 2009).