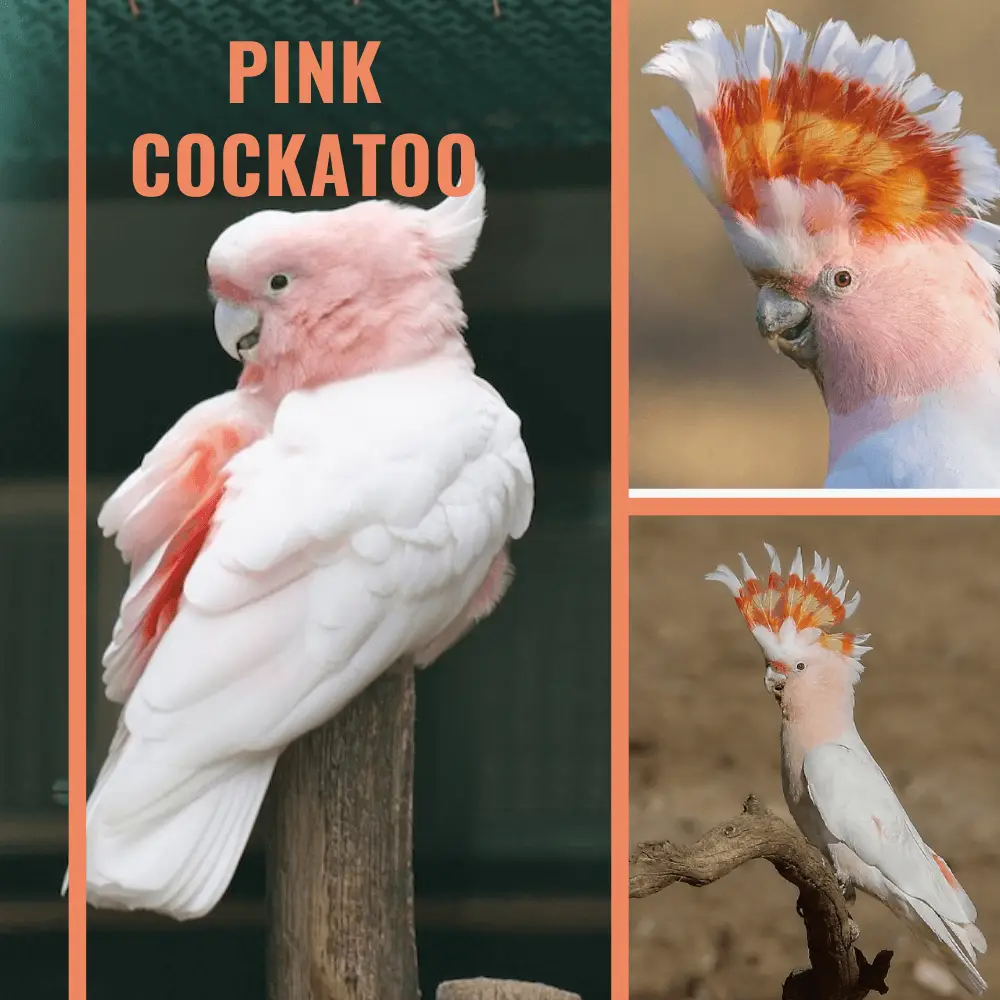

Pink Cockatoo: 33–40 cm; 360–480 g; female slightly smaller. Unmistakable within the Australian range. White, with pink sides of head, neck and underbody, and narrow pink-red band on the lower forehead;

white crest (125 mm long) with the broad orange-red band through centre enclosing a yellow stripe of varying width (broader in female); underwing white with the broad pink band in centre;

undertail white with an orange-pink wash in the centre; bill grey-black; feet grey; eye dark brown in male, juvenile and immature; female develops red eye when two years old. Young takes 3–4 years to reach maturity.

Systematics History

pink umbrella cockatoo

Editor’s Note: This article requires further editing work to merge existing content into the appropriate Subspecies sections. Please bear with us while this update takes place.

Sometimes placed in genus Lophochroa; a recent molecular study indicates that the present species is sister to the other members of Cacatua and may, therefore, merit generic separation.

Has hybridized in the wild with Eolophus roseicapilla. Formerly subdivided into three subspecies on basis of size and of the quantity and colouring of crest feathers, but the study of 22 wild-caught pairs and examination of museum skins showed that criteria for subspeciation could hardly be upheld;

form Mollis (C Western Australia to Northern Territory and W South Australia), with little or no yellow in the crest, is sometimes retained, but very poorly differentiated and not recognized here. Treated as monotypic.

Subspecies

Introduced around Sydney and, unsuccessfully, in Fiji.

SUBSPECIES

Lophochroa leadbeateri mollis Scientific name definitions

Distribution

W Australia

SUBSPECIES

Lophochroa leadbeateri leadbeateri Scientific name definitions

Distribution

C and ec Australia

Pink Cockatoo Distribution

Throughout much of inland Australia, from S Kimberley region (Western Australia) and EC Northern Territory S to CW coast near Geraldton and S coast at Eyre, then through inland South Australia (mainly in SC areas), NW Victoria and New South Wales to S Queensland.

Pink Cockatoo Habitat

Semi-arid to arid shrubland (mulga and mallee), with (especially Eucalyptus) tree-lined watercourses, where nest-hollows tend to be located;

also found in woodland, including cypress (Callitris), acacia and Casuarina. Mainly found in areas that receive 250–400 mm of rain per annum.

Families join a local nomadic flock during summer and spend autumn and winter wandering over 300 km². Flocks may number several hundred birds, and contain breeding and non-breeding birds, as well as occasionally other cockatoos (e.g. Eolophus roseicapilla and corellas).

Pairs begin to visit their nesting territories in Aug but return to forage with the flock. Considered to be only a vagrant in parts of Victoria (e.g. around Geelong and Wangaratta). Flight is rather slow and laboured compared with that of Eolophus or corellas.

Pink Cockatoo Diet

Like several other species of cockatoo, thrives on grain spilt during harvest and left lying on the stubble throughout winter, but the present species has a very strong bill and is able to extract seeds from a wide variety of native species, e.g. Callitris, Casuarina, Ficus, Grevillea, Hakea, Proboscidea, Santalum, Acacia, Eremophila and Codonocarpus.

Many of these species fruit irregularly and the plants are scattered over a large area, and as a result, one benefit of feeding in flocks of 20–50 birds is that older members of these long-lived animals can probably remember the locations of these scarce resources.

Piles of debris are left on the ground after the flock has exploited rich food resources. Besides waste cereal grain, species eat seeds of a number of weeds, such as Emex and various wild melons (Citrullus, Cucumis).

Insect larvae are extracted from branches of various eucalypts, acacias and Codonocarpus. Visits waterholes to drink early morning and late afternoon, or more regularly at other times of day during extremely hot periods.

Pink Cockatoos flying drinking feeding

SOURCE: Echidna Walkabout Nature Tours

Pink Cockatoo Sounds

Principal vocalization recalls that of C. sanguinea, but is a less raucous quavering falsetto “quee-err”; also gives a harsh alarm call, while fledglings utter constant wheezing when begging for food and adults make soft chattering notes during courtship.

Pink Cockatoo Breeding

In early Aug, pairs return to their traditional nest-hollows; laying Aug–Oct, but nesting sometimes commences in May in N Australia.

Nest-hollow (3–20 m above ground, usually in eucalypt) renovated by both sexes, which chew the sides to make a bed of woodchips, sometimes also containing pebbles; neighbouring nests rarely closer together than 2 km, and nests usually sited near water.

Clutch of 2–5 white eggs laid (mean 3·3 in one study), at intervals of 2–3 days; incubation 23–26 days, by both parents, usually starting with a third egg laid; chick has vestigial, short buffy-white down; nestlings remain in the hollow for c. 57 days (53–66), and fed thereby both parents; brooded by the male by day and female at night.

The family remains together near the nest until all nestlings have fledged, then joins other families in a local flock at a suitable food source; juveniles continue to be fed by their parents (mainly by the male) for at least three months.

Productivity in Western Australia is as follows: 75% of eggs hatched, with 11% of clutches failing, but success rates of 60% (from egg stage) and 80% (of eggs that hatch), and mean 1·56 young fledged per nest.

Sometimes a pair needs to evict a pair of (smaller) Eolophus roseicapilla that has moved in over the winter and starts to lay; occasionally a mixed clutch of these two species results and is incubated; when this mixed brood fledges, the E. roseicapilla grows up behaving as if it were a member of present species, ignoring conspecifics.

are cockatoos good pets

How much does cockatoos cost

Hink Cockatoo Price

this species of Cockatoo can cost between 1,000$ and 2,000$.

Conservation Status

Not globally threatened. CITES II. Previously considered Near Threatened and was even speculated to be possibly meritorious of categorization as Vulnerable, but insufficiently known on a continental basis.

Clearing for agricultural development has stopped in all states except Queensland. Local declines were reported as a result of habitat clearance and trapping, although overall numbers (speculated to be c. 20,000 in the 1990s) were thought to be stable.

Out-competed for nest-sites by Eolophus roseicapilla in some areas and, as latter species spread, this may represent a problem in future. Known from several conservation units, including Wyperfield National Park (Victoria), were described common, and Warrumbungle National Park (New South Wales).

The formation of large flocks in autumn and winter renders present species particularly susceptible to poisoning or trapping; although such flocks appear large, they represent all ages from a very large area, so that the small proportion of young recruits may be obscured; this could lead to complacency, and populations need to be monitored.