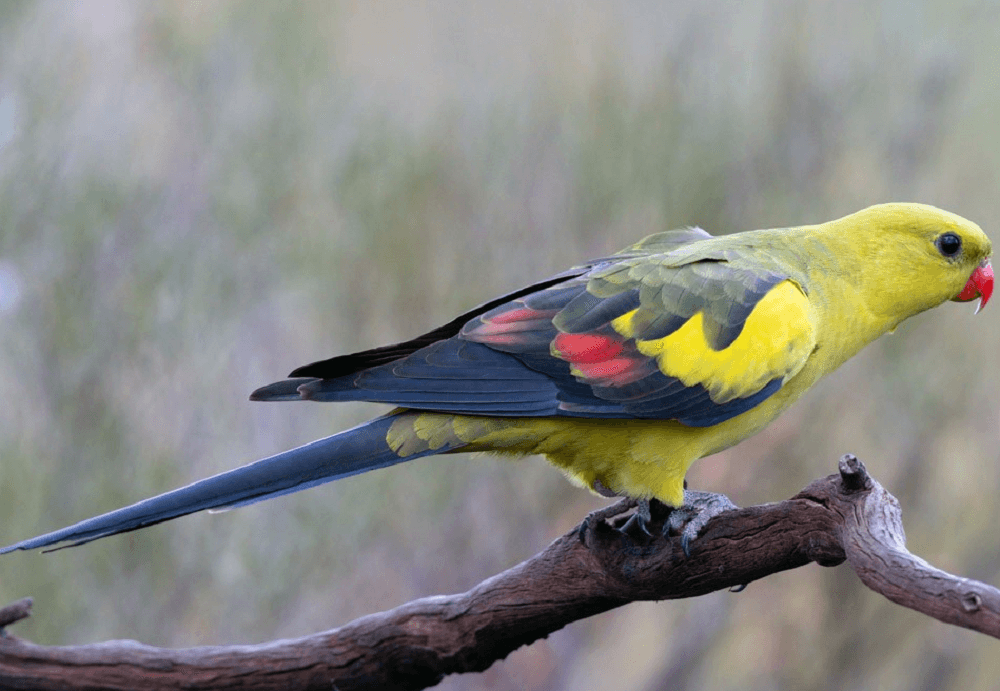

Regent Parrot 40 cm; mean 114 g. Bill pinkish red; head pale yellowish olive, shading to dark olive on the mantle, back, and scapulars; underparts, rump, and lesser and median wing-coverts bright yellow;

the remainder of wing blackish except for broad red band on inner secondary coverts and red tips to inner secondaries; tail blue-black. Female Regent Parrot duller and much greener. Immature similar. Race monarchoides has less olive head and breast

.Polytelis anthopeplus Scientific name definitions

- LC Least Concern

- Names (14)

- Subspecies (2)

Systematics History

Editor’s Note: This article requires further editing work to merge existing content into the appropriate Subspecies sections. Please bear with us while this update takes place.

Forms a parapatric Regent Parrot pair with P. swainsonii. E race erroneously listed as nominate in past, with W Parrots placed in race westralis; with correction of the type locality, latter becomes a junior synonym of nominate. Two subspecies were recognized.

Subspecies

SUBSPECIES

Polytelis anthopeplus anthopeplus Scientific name definitions

Distribution

SW Australia.

SUBSPECIES

Polytelis anthopeplus monarchoides Scientific name definitions

Distribution

interior W part of SE Australia (SE South Australia, SW New South Wales, and NW Victoria).

Distribution

Editor’s Note: Additional distribution information for this taxon can be found in the ‘Subspecies’ article above. In the future we will develop a range-wide distribution article.

Habitat

Regent Parrot In SE Australia, flooded-zone Eucalyptus woodland and adjacent arid mallee scrublands, with breeding, always taking place within 20km of mallee or cultivated land; in SW, most types of wooded land include partly cleared areas in dense coastal forest.

Movement

Northward post-breeding dispersal in SE Australia, while in SW there is evidence of seasonal (commoner May-Dec than Jan–Mar), irruptive and nomadic behavior, apparently depending on the regularity of rains, with certain well-watered core areas being occupied year-round.

Regent Parrot Diet

In SE of range formerly fed extensively on seeds of native hops Dodonaea attenuata and D. viscosa, now much reduced by human settlement;

still feeds primarily in mallee, on seeds of Eucalyptus, Acacia, grasses (five wild Poaceae recorded) and herbaceous plants (five Asteraceae, four Chenopodiaceae, two Cucurbitaceae, two Dilleniaceae), plus fruits (e.g. Ficus and Amyema mistletoe), leaf buds, blossoms, and green shoots; also wheat and cultivated fruits, thus sometimes a crop pest in fields, vineyards and orchards.

Regent Parrot Behaviour

The commonest vocalization is a rolling, grating “currack”, typically repeated by all members of a flock (similar to P. swainsonii but sounding slightly harsher).

Breeding

Aug–Jan, also May. Usually in small loose colonies of up to 67 pairs; of 57 nests in one study, 45 were within 150 m of another nest.

Regent Parrot Nest is an often deep hollow in the main trunk of tree, commonly salmon gum (Eucalyptus salmonophloia) and wandoo (E. wandoo) in SW Australia, E. camaldulensis in SE;

hole always above 4 m, and sites always within 5 km of blocks of mallee. Eggs 4–6; incubation lasts 21 days; nestling period c. 6 weeks.

Conservation Status

Conservation status on BirdlifeLC Least Concern

Not globally threatened. CITES II. Now very uncommon in SE Australia, retreating before clearance of mallee for agriculture, but abundance in fact initially increased in SW as a result of human occupation of the Wheatbelt, with flocks of up to 100 reported.

However, the substantial decline since the 1940s throughout the Wheatbelt, probably as a result of loss of nest-sites, possibly compounded by an open season in five shires of Western Australia to control numbers invading croplands; recent signs of increasing numbers.

Poor regeneration of nest trees is certainly a long-term cause for concern; the Regent Parrot needs large, old gums near water, and additionally, these must be acceptably close to the feeding habitat.

Competition for nest sites with feral honey bees appears not to be significant, but there is some overlap in site preference. In SE Australia, roadkills while taking spilled grain common, and occupation of nests by feral bees problematic.