Systematics History

Monotypic.

Subspecies

Monotypic.

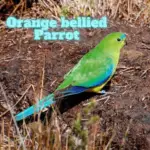

Distribution

SE Australia from inland SE Queensland S to NC Victoria.

Habitat

Open forest, woodland, native grassland, with a marked preference for ecotones between open and closed habitats, e.g. heath-forest ecotone and adjacent farmland.

In Victoria, the Turquoisine Parakeet has a positive association with Eucalyptus albums which reflects this parakeets high use of rocky ridges in winter, moist flats and gullies from spring to autumn, and SE slopes year-round.

Movement

Apparently mainly sedentary but with local post-breeding dispersals and irregular local movements probably in response to rainfall.

Reappearance in part of the former range in 1994–1995 was judged a nomadic response to drought conditions elsewhere rather than a recolonization.

Diet and Foraging

A generalized diet consisting of seeds, flowers, and fruit of both native and introduced plants including grasses, composites, other herbs, and shrubs:

records include seeds or fruits of Leucopogon microphyllus, Stellaria media, Briza minor, Hordeum murinum, four species of Danthonia, Stipa, Urtica urens, Hypochoeris glabra, Carthamus lanatus, Dianella revoluta, Geranium, Sisymbrium, Paspalum, Pulteneae procumbens, Dillwynia retorta, Brachyloma daphnoides, Hibbertia stricta, flowers of Grevillea Alpina, moss spore cases and spilt sorghum by roadsides.

Turquoise Parrot – Capertee Valley

SOURCE: BIBY TV

Sounds and Vocal Behavior

Turquoisine Parakeet Calls include single and double high-pitched tinkling notes such as “tse” and “tsink”. When flushed a similar or slightly buzzier tree.

Turquoisine Parakeet Breeding

Aug–Dec, with one area producing records also in Apr-May, presumably second broods. Turquoise Parakeet Nest in a hollow in the tree (Eucalyptus in at least Victoria), stump, fence post, or fallen log.

Turquoise Parakeet Eggs 4–5 (2–6); incubation lasts c. 20 days; nestling period c. 4 weeks.

Turquoise Parakeets as Pets

SOURCE:Love of Pets

Conservation Status

Not globally threatened. CITES II. Currently considered Near Threatened.

A dramatic decline to near-extinction occurred from 1880 to 1920, attributed to the effects of habitat clearance and modification by introduced herbivores (cattle, sheep, and rabbits), compounded by the impact of a major drought in 1902 and possibly by trapping;

but after 1930 (and particularly after 1970) numbers recovered rapidly, and the species is currently locally common, albeit in disjunct areas.

Good numbers in various reserves suggest that grazing indeed seriously disrupts foraging ability; however, the fall and rise in numbers was so sharp that possibly an epidemic was involved. In Victoria, a lack of appropriate breeding hollows may be restricting population growth.

SOURCE:Bird Spy Australia